There I was, stuck in Beijing during yet another wave of the COVID-19 Novel Coronavirus, when I felt an irresistible urge to break quarantine. For some strange reason it seemed like most of the tourist sites had been kept open this time around, as opposed to just a few short months before when they’d been sealed off completely. My mind made up, I turned off the Tiger King episodes I’d been binging and prepared to break free from the locked-down Traveling Circus. One quick glance at my Middle Kingdom Bucket List showed there was still one more tourist attraction I had yet to explore, and this one was a doozy.

It was the Holy Grail of Communist Propaganda Museums.

It was the White Whale of Revisionist Historical Sites.

It was 中国人民革命军事博物馆… aka, The Military Museum of the Chinese People’s Revolution.

But it seemed like just as soon as I’d set my mind on the destination, I began to encounter obstacles. See, for as much as this place would love to consider itself the Far East’s answer to America’s Air & Space Museum, you just can’t rock up to the gate and stroll in.

I should know; I tried.

On my first attempt at a visit, one of the helpful guards informed me that the city of Beijing had enacted rules to limit the museum’s occupancy during this “exceptional time.” Basically, all visitors were now required to book an appointment window at least one day in advance through the WeChat smartphone app. So in an attempt to comply with the local public health guidelines, I headed back home and did my best to follow the guy’s instructions, but still hit a brick wall. See, the museum’s appointment system was based around a person’s 身份证. The 身份证, as we all know, is the national identity card issued to all Chinese citizens, and because I didn’t have one I was simply excluded from booking a visit.

After about a week of grumbling, during which I was fixated on the irony of a straight white guy getting caught up in a web of institutionalized discrimination, I finally caught on to the fact that the museum also had a good old-fashioned website. Online, I was able to create a guest account using my passport number, and then link it up to my own WeChat account and local phone number, 身份证 be damned! Fingers crossed, I took another stab at a booking… and hot damn, wouldn’t you know? I was in!

So the very next Sunday, when I strolled back up to the gate with my shiny new QR appointment code, that same guard waved me right on inside. When I tried to thank him for his help, though, I’m not sure he recognized me. Who knows, maybe all us foreigners look alike?

But anyway, once inside the gate, there was one last, long queue for security screening. Or should I say, there was a long queueing area set up, with rows of winding stanchions leading into a tented area… with absolutely nobody else in line! On a smoggy, rainy, weekend afternoon– the perfect day for a museum visit– apparently I was the first customer of the day. I resisted the urge to sprint through the process, seeing as how there were about twenty other guards there staring at me. Honestly, I can’t blame them, since it didn’t look like there was much else to do. I obediently sent my bag through the X-Ray machine, waited patiently as nobody bothered to glance at the display screen, then glided through the metal detector even as my keyring set off the alarm. Thesupervisor shot me a bored glance before dismissing me with a wave… and just like that, I had arrived!

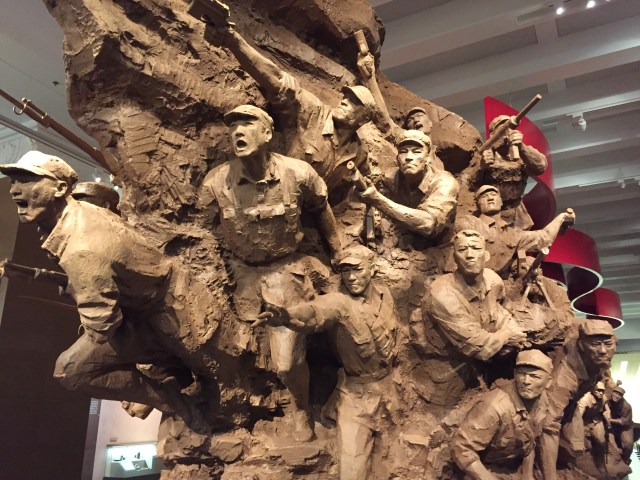

And even though it turned out that I wasn’t technically the only visitor that day, there were fewer than ten of us, so it sure did feel like I had the entire place to myself. This huge, cavernous building was also occupied by about a hundred or so college-aged docents, all of them looking not too thrilled about working on the weekend, and all of them doing their best to duck away from the security cameras when texting on their cell phones. And I couldn’t tell whether they were truly suspicious of me as a foreigner, or whether they were just paying more attention to their guests during the ongoing pandemic, but whatever the reason, I was openly shadowed for the next two hours. I got the distinct impression that this place wasn’t used to receiving too many Westerners at all, especially since the display signs were all written in Chinese. The entire museum– all five floors of it, or six, counting the basement– seemed geared towards inspiring a peculiar sense of nationalism.

All in all, this visit turned out to be a really satisfying day at the museum, if not necessarily an informative one. Although a few days later, when I was chatting about my experience with a local friend, they confided in me that “军博” was designed with a more youthful audience in mind. Apparently, schools and summer camps regularly bus in large groups of students from around the country, or at least they did during more “normal” times. No child’s compulsory military training sessions are complete without a trip to ““军博”, so I guess this place is as much an indoctrination point as it is a tourist attraction.

And you know, that might help explain the noticeable absence of a gift shop…